The black and white photo at the entrance of the the Himeyuri Peace Museum in Naha, Okinawa, shows the graduating class of 1944.

The 50 or so young women, aged 15-19, are grouped around their principal, smiling brightly into the camera and their own futures. They are the most promising female students in the Okinawa Prefecture, chosen to attend the schools collectively known as Himeyuri, a teacher preparation college and a girls’ high school.

As WW II raged on, the girls had become aware of the militarization of their education. English studies were suspended. They were taught to hate and fear Europeans and Americans, and to swear absolute loyalty to Japan’s emperor, to believe that death was a more honorable choice than to surrender. Their uniforms became simpler, made from cheaper fabric, as resources in Japan were depleted by the war effort.

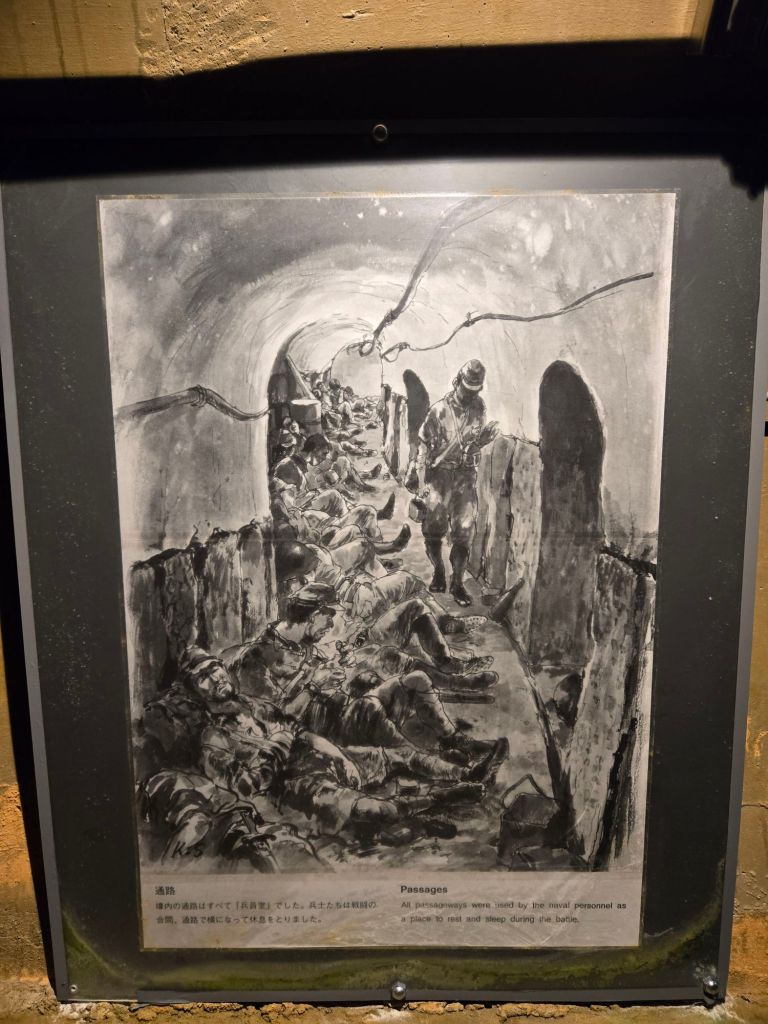

In March 1945, the US began shelling Okinawa, determined to capture the island as a base from which to attack mainland Japan. The Japanese, equally intent on delaying the invasion of Okinawa to buy Japan more time to prepare for an American assault, dug into a series of underground tunnels, which would eventually house 4000 men.

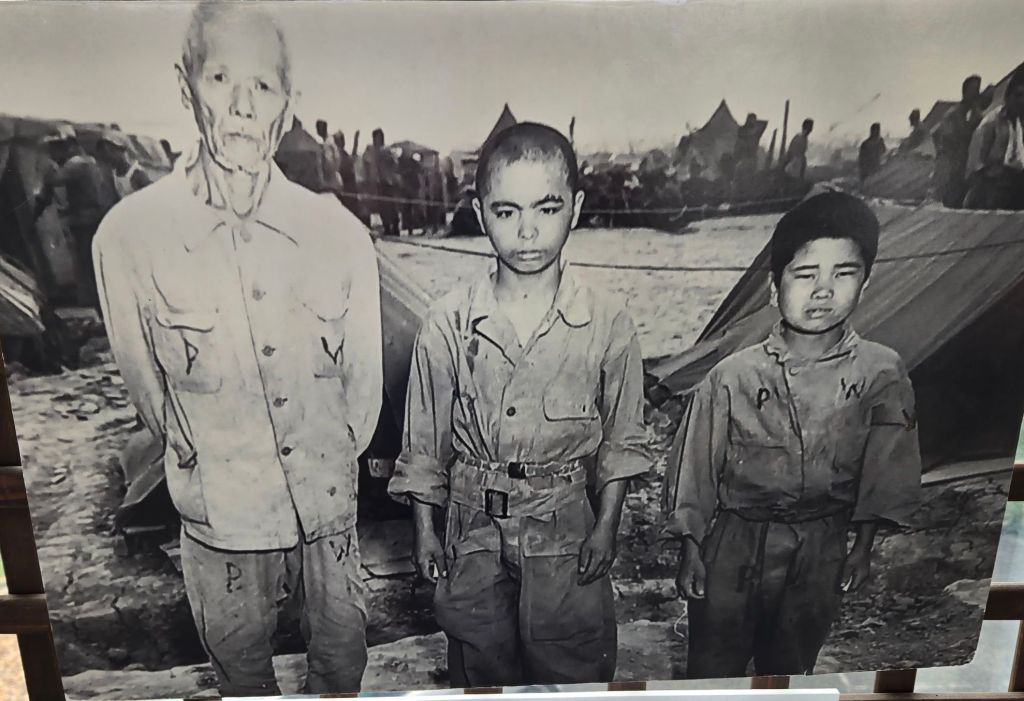

Hopelessly outmanned and outgunned, the Japanese army resorted to nighttime attacks on American positions, armed only with spears. They conscripted elderly men and young boys in an attempt to swell their ranks.

As Japanese casualties mounted, Japan also recruited the girls and women of Himeyuri, telling them they were needed as nurses in a field hospital. The students and teachers packed up their books and journals, believing they were being deployed to an official Red Cross hospital, and would still have time to read and write during breaks in their shifts.

Instead, they were led to a cave where injured Japanese soldiers were being brought for whatever help could be given under the most primitive of conditions. The women were assigned the filthiest, most dangerous tasks, which included leaving the cave to find food and water during the American assault. They had no breaks, and learned to sleep, quite literally, standing up.

As it became obvious that the Japanese were going to lose the Battle of Okinawa, the women were ” decommissioned,” told their services were no longer needed, and left to fend for themselves. They were barred from finding refuge in other caves being occupied by the Japanese military. Many were killed or took their own lives.

Back in the underground tunnels, Admiral Minoru Ota, the Japanese commander, realized not only that the battle was lost but that the sacrifices his troops had demanded of the Okinawans were unforgiveable. In a telegram to his own commanding officer, dated June 6, 1945, he acknowledged that ” ever since our Army and Navy occupied Okinawa, the inhabitants of the Prefecture have been forced into military service and hard labor while sacrificing everything they own as well as the lives of their loved ones. They have served with loyalty…but they will go unrecognized, unrewarded. Seeing this, I feel deeply depressed and am at a loss of words for them….And for this reason, I ask you to give the Okinawan people special consideration, this day forward.” A week later, he and his staff took their own lives.

More than a third of the population of Okinawa was killed during this battle, which took the lives of more than 200,000 people on both sides.

The women of Himeyuri who somehow managed to stay alive remained silent about their experiences for years, many wracked by survivor guilt. Eventually, however, they realized that the best way to honor their classmates and teachers was to tell their stories, and the Himeyuri Peace Museum was established in 1989. Today, visitors can tour exhibits, listen to interviews, and pay their respects with bouquets. Just before the exit, a piece of music called ” The Farewell Song,” composed for but never played for the Himeyuri graduating class of 1945 ushers visitors back outside.

The day we visited, most families had young people with them, who, I hope, will ensure that the futility of battles like the one that ravaged Okinawa can be avoided in the future.

Postscript: Today, April 11, 2024, an article from the National Public Radio entitled “Okinawa feels impact of U.S. and Japan military shifts” popped up in my news feed. Apparently, “Okinawa… is the focus of U.S. and Japanese efforts to beef up defenses in Japan’s southwest islands” to ward off potential attacks from China.

It apoears that the special consideration Admiral Ota requested for Okinawans almost 80 years ago is being ignored. The line “When will they ever learn? has never seemed more appropriate.