The elderly man sitting in front of me in the tundra buggy leans over and says quietly into his wife’s ear, “How much longer until we see some polar bears?”

She points to the horizon, where another tundra vehicle filled with tourists is trundling up a hill. “I think that’s where we’re going, dear, so it might be a while yet.”

Our buggy driver Jim wasn’t kidding when he said that polar bear watching is not for the impatient. At 6:30 this morning, we joined 118 fellow travellers for a two-hour charter flight from Edmonton to Churchill, Manitoba, a community of 900 people perched on the western shore of Hudson’s Bay. A fleet of buses then took us 20 minutes down the road to the parking lot of Tundra Buggy Adventures, where we were sorted into groups of 40 and ushered on board the heated vehicles. Jim, our bearded, storytelling, driver and guide, schooled us in polar bear watching protocol – no flash photography out the windows, no eating or drinking on the outdoor observation deck, no loud noises when polar bears were in the vicinity, no hogging the best vantage points for photographs.

“And don’t forget you’re my eyes while I’m driving this thing. I’ll be too busy keeping us out of the ditches, so if you see a bear, use the o’clock system to let us all know where to look and I’ll do my best to stop.”

We start out on what Jim called the “super highway” – a relatively flat, smooth stretch of terrain that lasts only a few hundred meters. After that, we slow to a glacial pace, bumping over rocks and frozen mud ruts, breaking through iced-over dips in the road. Sometimes, Jim advises us to “get a leg out into the aisle”as the uneven terrain pitches the buggy precariously over to one side. We stare out the windows, scanning the horizon, but there really isn’t much to see except a black and white study of snow, stones, and clumps of willow shrub.

“8 o’clock!!!”

What? Where? All eyes pivot to the back of the bus, and we squint in the direction our fellow passenger is pointing. Rapid but quiet scramble to the outdoor observation deck as one by one we spot the white shape, head down, ambling beside a distant willow clump. He doesn’t hang around long, though, disappearing from view almost before you could say telephoto lens, much less get one trained on him.

We settle back into our seats, our appetites whetted by this early sighting. It isn’t too much longer before we see more movement, this time out of photograph range – a mother and cub, travelling together, and a lone male bear well behind them, but heading in the same direction. The cub suddenly takes off along the shoreline at a gallop, while its mother rounds to face the male, who immediately retreats.

“That’s a good mom, good instincts,” says Jim. “They’re not all like that. I remember seeing a young sow with a cub a few years back. She passed right by a male, didn’t even look around. A few minutes later, the male attacked the cub, killed it. Nature isn’t anything like Walt Disney.”

Half an hour passes with no more bears in sight. Jim taps into the radio chatter between the other buggy drivers and decides we’ll head over to Polar Bear Point, where Tundra Buggy Adventures has its lodge, a four-trailer, overnight accommodation for those who want more than the one-day version of the tour we’re taking. On the way, we pass Tundra Buggy 1, which is owned by Polar Bear International, an organization designed to “conserve polar bears and the sea ice they depend on.” Unlike us, they track the movements of a few polar bears all day, operating a live webcam that can be accessed around the world. “We want people to care about polar bears,” says Jim, “because you can’t care for what you don’t care about.”

Judging by the number of tundra buggies congregated near the lodge when we finally arrive, we figure there have to be polar bears close by. And then we see them, right next to the road – four males lounging around in the underbrush. They appear to be moving about as fast as we had for most of the morning, so Jim decides this would be a good place to park for lunch. We settle in with our soup and sandwiches to see what interactions might occur between the bears.

Unlike us, these guys haven’t eaten for four months, and won’t until they can get out seal hunting on the Hudson Bay ice, so it’s no wonder they’re lethargic. But then two of them sit up, nudging muzzles, showing off their tonsils, and generally trying to get each other’s attention.

Photo credit: Lorne Dmitruk

Photo credit: Lorne Dmitruk

Photo credit: Lorne Dmitruk

And then, like a pair of rambunctious teens, they begin to spar, a friendly behavior that will turn much more aggressive in later life when as older males they begin competing for female attention.

After the show is over and the bear buddies amble off, Jim starts up our buggy and weaves through the other parked vehicles to see who else might be hanging around the shore. I’m glad when someone across the aisle from me asks the question that had been on my mind ever since we’d arrived: with all the buggy traffic, could we actually be bothering the bears, rather than just observing them?

Jim says that one study had shown about 5% of polar bears display a negative response to the vehicles that lumber through their territory. “You might not realize it, but we’re actually in kind of a reverse zoo situation here. We’re the ones in the cages, and the bears decide if they want to be bothered to take a look at us.”

The last two bears we see prove his analogy. We pull up within a few metres of one who is snoozing with his paw over his nose. We stay there several minutes, but he never moves. Only when Jim starts up the engine does he slightly open his eyes, as if to watch our departure.

Just a little further down the road, we park behind another tundra buggy, its observation deck full of people pointing across the tundra. Coming towards us at a slow but determined pace is a large male, clearly interested in taking a closer look at us.

He hangs out for several minutes before deciding that we’re not that interesting. Shooting us a couple of backwards glances, he heads off across the ice, and disappears.

I wish him, and all the other bears we’ve seen today , a safe and productive winter. We’ve heard some sobering information about polar bear habitats. As global warming continues at an unprecedented rate, the ice which provides hunting platforms for the bears is dwindling. Ringed seals, the bears’ main food source, are also in shorter supply as their snow-covered birthing lairs are more frequently collapsing from overly warm winter weather, or being washed away by rain. Without seal fat in their bodies, polar bears are not only prone to starvation, but the females are less likely to give birth. Jim told us that in the years he’s been a buggy driver, he’s seen fewer and fewer bears in the Churchill area.

So what can we do to increase polar bears’ chances of survival? Visit the Polar Bear International website for a long list of ideas, from adopting a bear to lobbying governments to take action against climate change. Scientists now know that human activity has negatively impacted the polar bears’ habitat. But if we act quickly, we can also reverse some of the damage, and ensure that future generations can experience the awe of flying to Churchill and interacting with these Lords of the Arctic.

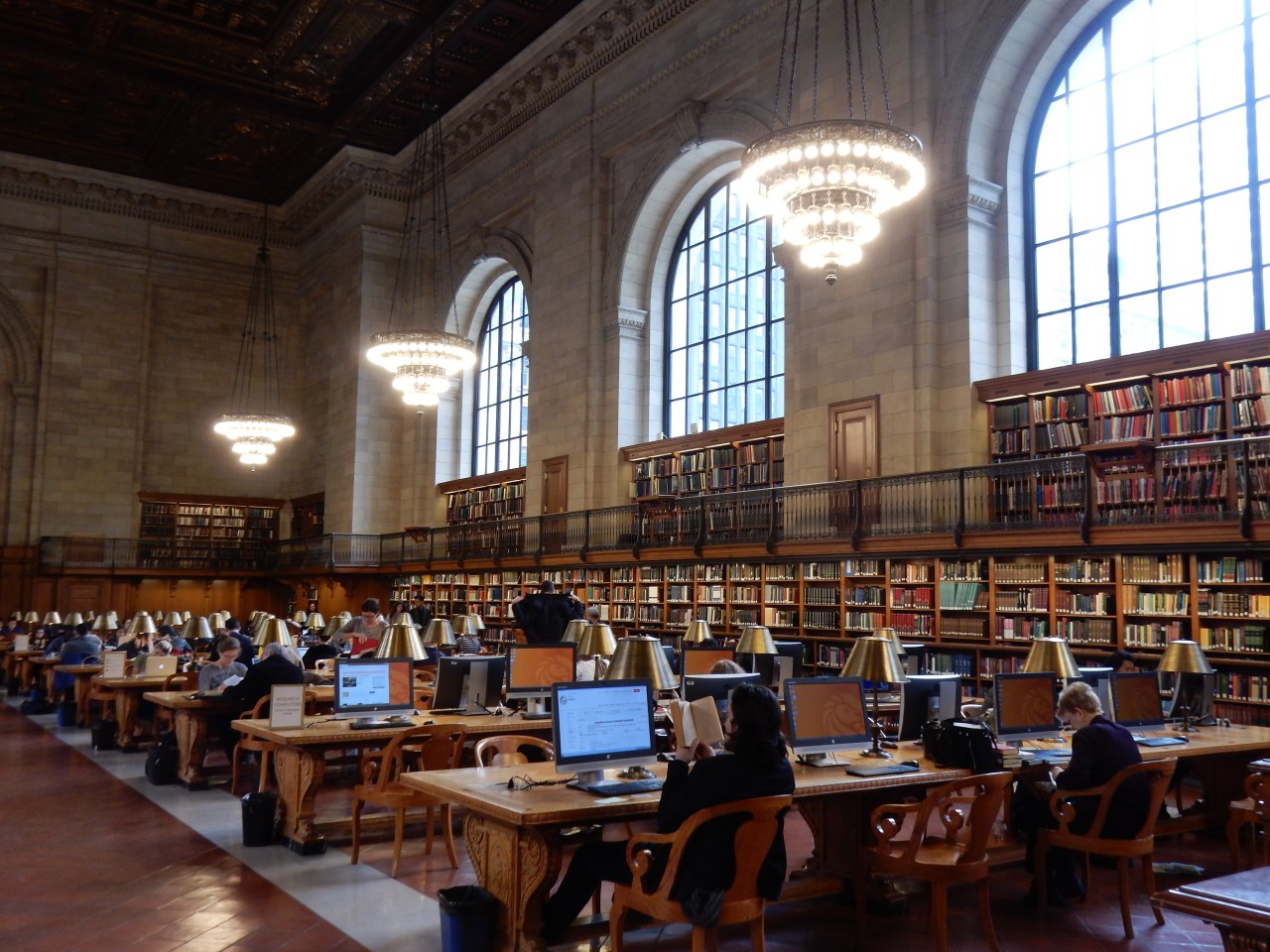

But the library is not intended only for serious adult patrons. The charming children’s room features a stimulating space for little readers and their caregivers. They can even visit Christopher Robin Milne’s original stuffed animal collection – Winnie-the-Pooh, Kanga, Piglet, Eeyore, and Tigger – the inspiration for the classics by Christopher’s father, A.A. Milne.

But the library is not intended only for serious adult patrons. The charming children’s room features a stimulating space for little readers and their caregivers. They can even visit Christopher Robin Milne’s original stuffed animal collection – Winnie-the-Pooh, Kanga, Piglet, Eeyore, and Tigger – the inspiration for the classics by Christopher’s father, A.A. Milne.

But there are 16 voices associated with the tragedy that New Yorkers are not only listening to but celebrating, embracing, coming back to hear again and again. They are the cast of the Canadian musical

But there are 16 voices associated with the tragedy that New Yorkers are not only listening to but celebrating, embracing, coming back to hear again and again. They are the cast of the Canadian musical

In honor of the lunar New Year – we have many students from China studying in our faculty, and people of Chinese heritage make up seven per cent of our city’s population – we gathered in the atrium of our building to eat, play games, make decorations, and talk. A visiting Uruguayan professor introduced his wife and daughter to one of our Argentinian-born instructors, who had brought her daughters to enjoy the fun. Students from Africa and Japan crafted paper lanterns together. A husband and wife from Kazakhstan, enrolled in English language classes, chattered in Russian and giggled as they tried to pick up marbles with chopsticks.

In honor of the lunar New Year – we have many students from China studying in our faculty, and people of Chinese heritage make up seven per cent of our city’s population – we gathered in the atrium of our building to eat, play games, make decorations, and talk. A visiting Uruguayan professor introduced his wife and daughter to one of our Argentinian-born instructors, who had brought her daughters to enjoy the fun. Students from Africa and Japan crafted paper lanterns together. A husband and wife from Kazakhstan, enrolled in English language classes, chattered in Russian and giggled as they tried to pick up marbles with chopsticks.

It was one of those serendipitous e-mails that made my heart sing: my friend Livia was going to be in Brussels at the same time I was.

It was one of those serendipitous e-mails that made my heart sing: my friend Livia was going to be in Brussels at the same time I was. in Belgium.”)

in Belgium.”) leftover monument from the 1958 World’s Fair; the glittering guild halls of the Grand Place. So the time I spent with Livia would centre around girlfriend walking and talking with Brussels as our backdrop.

leftover monument from the 1958 World’s Fair; the glittering guild halls of the Grand Place. So the time I spent with Livia would centre around girlfriend walking and talking with Brussels as our backdrop.

On the Wednesday before our Saturday departure from Rarotonga, someone at breakfast dares to raise the subject.

On the Wednesday before our Saturday departure from Rarotonga, someone at breakfast dares to raise the subject. Although we glimpse each other once in a while on the flight to Los Angeles, and again in the LA airport as we kill time before travelling to our home destinations, our little Raro travel community quietly dissipates. Sixteen hours later, my husband and I arrive home to a dark house, and minus 10 C. Two days after that, I’m waiting in my parka at 7:45 a.m., not to flag down Rarotonga’s clockwise or counterclockwise coach, but to board a regularly scheduled, on-time, Edmonton Transit bus to go to work.

Although we glimpse each other once in a while on the flight to Los Angeles, and again in the LA airport as we kill time before travelling to our home destinations, our little Raro travel community quietly dissipates. Sixteen hours later, my husband and I arrive home to a dark house, and minus 10 C. Two days after that, I’m waiting in my parka at 7:45 a.m., not to flag down Rarotonga’s clockwise or counterclockwise coach, but to board a regularly scheduled, on-time, Edmonton Transit bus to go to work. I’m more in favor of finding ways to bring together our vacation selves with the sometimes Storm Trooper realities of our back-home lives. Even though Rarotonga’s temperatures won’t be visiting Edmonton for six more months, the Pacific Ocean is entire province away, and speakers of Cook Islands’ Maori are as scarce as palm trees, I’ve discovered a few ways to keep the rareness of Raro alive during real life back in Edmonton.

I’m more in favor of finding ways to bring together our vacation selves with the sometimes Storm Trooper realities of our back-home lives. Even though Rarotonga’s temperatures won’t be visiting Edmonton for six more months, the Pacific Ocean is entire province away, and speakers of Cook Islands’ Maori are as scarce as palm trees, I’ve discovered a few ways to keep the rareness of Raro alive during real life back in Edmonton.