Reading, photos – what could be better?

Of bonnets and sonnets and Easter parades

It’s hard to remember now when crowded streets brought joy rather than anxiety.

Thanks goodness for photos and blog posts.

Seven years ago, my friend Angela and I headed out on a warm Easter Sunday afternoon to mingle with other Easter bonnet revelers on 5th Avenue, to see and be seen. Here’s my record of that experience, with wishes for the return of the Easter parade and a happy Easter to those of you who observe it.

New York City’s Easter Parade down 5th Avenue is more than a hundred years old. It has evolved from its late 19th century elegance to its current incarnation – a 10-block promenade where the cute and the zany, the heartwarming and the gawdy, the innovative and the traditional compete for the attention of onlookers, photographers, and other participants. It is five hours of smiling, good-natured fun that needs only a few lyrics from Irving Berlin to accompany it and no further commentary from me.

I climb onto the Middlebury College van for the third consecutive afternoon, grateful for a few hours in the town of Middlebury itself, away from the pretentious Vermont writing conference I’ve paid too much money to audit. And for the third day in a row, the same blonde woman with the open face and relaxed smile is also on board the van, looking out the window at the back.

Today, I sit across from her and ask how she’s enjoying the conference. She rolls her eyes. “Whoever heard of gathering hundreds of people together, taking their money, and then telling them they aren’t here to actually write? We’re supposed to worship at the feet of a bunch of mostly white male writers, listen politely, and improve our craft by absorbing their pearls of wisdom? Please.”

I like her immediately. For the next two weeks, Angela and I meet on the van every afternoon, wander the Middlebury shops, talk, and have coffee. At the end of the conference, she invites me to visit her in Manhattan, and the next spring, I show up on the doorstep of her five-storey, Upper West side brownstone. This is the first of several trips I’ll take to NYC between 1995 and this week, the 20th anniversary of my friendship with Angela.

During previous visits, I’ve seen many of the top ten New York tourist sights, so this trip is all about seeking out less obvious, more hidden attractions. It seems only appropriate to begin our five day ramble of Angela’s city with a trip to the New York Historical Society Museum. In spite of the Easter weekend tourist crowds on the sidewalks outside, few people are finding their way inside this relatively little known gem of New York memorabilia. We start our tour with a 15 minute, multiscreen, multimedia film, and then head to the top floor which is jammed with furniture, military artifacts, the belongings of all manner of American who’s who, paintings, and sculptures.

Angela points out some of the pieces that speak to her – the desk where Clement Clark Moore wrote “The Night Before Christmas,” George Washington’s camp cot, sculptures depicting the daily business of the slave trade.I find my own favorites : a cast of Abraham Lincoln’s hands, one swollen after a day of hand-shaking, the other stretched around a cane to make it look more attractive – and the remnants of more recent heroes, the men and women who responded to the aftermath of the 9-11 tragedy.

We could have spent much longer poring over the artifacts, but since we have tickets to a 2 p.m. off-Broadway show in less than three hours, we decide to move along to the feature exhibit, a display entitled Facades, by famed New York photographer Bill Cunningham. Cunningham, who is often seen pedalling around the city on his bicycle, looking for eye-catching examples of what he calls “street fashion,” worked on the project between 1968 and 1976 with his friend, fellow photographer, and “well-seasoned human being” Editte Sherman.  Cunningham captures Sherman posing in elegant vintage costumes with some of New York’s most stunning architecture in the background. Angela and I smile at Sherman’s panache and marvel at Cunningham’s gift for drawing subtle visual comparisons between Sherman’s style and the architectural features that provide a backdrop for her poses.

Cunningham captures Sherman posing in elegant vintage costumes with some of New York’s most stunning architecture in the background. Angela and I smile at Sherman’s panache and marvel at Cunningham’s gift for drawing subtle visual comparisons between Sherman’s style and the architectural features that provide a backdrop for her poses.

Our final stop in the museum has to be the giftshop. We flip through books and giggle over greeting cards. We ooh and aah over purses, scarves and jewellry, and strike a few poses of our own.

A quick subway ride later, and we’re in funky Greenwich Village, looking for anywhere near our theatre venue that will guarantee us an in-and-out lunch in 30 minutes. A Cuban place, its door open to the bright sun, loud with merengue and Saturday shoppers, slips salads and yucca fried in garlic and butter onto our table in less than half that time. We whirl away down the street to the Gym at Judson, where we’ll see I Remember Mama, in which ten elderly actresses play more than 20 roles in the story of a young writer, growing up in eariy 20th century San Francisco as part of a Norwegian immigrant family.

We are entranced by the venue – a church gymnasium, where we sit around the perimeter, and watch the play unfold at various dining room tables, covered in typewriters and coffee cups, antique linens, old letters, volumes of literature, and cookbooks. The play warms our hearts: Angela and I see some of our own experiences as writers and women played out around those tables, especially the growing realization that the most impactful writing happens when we mine the details of our own lives and present the stories we find there with insight and authenticity.

We are entranced by the venue – a church gymnasium, where we sit around the perimeter, and watch the play unfold at various dining room tables, covered in typewriters and coffee cups, antique linens, old letters, volumes of literature, and cookbooks. The play warms our hearts: Angela and I see some of our own experiences as writers and women played out around those tables, especially the growing realization that the most impactful writing happens when we mine the details of our own lives and present the stories we find there with insight and authenticity.

After the play, there are more performances waiting for us across the street in Washington Square Park. Among the daffodils and cherry blossoms, spring strollers, lovers, readers, musicians, and gymnasts stake out a piece of grass or cement, a park bench or a blanket. A woman with a gigantic bubble maker delights children of all ages.  Tables of chess players pore over their games, discuss politics, or provide strategy lessons to up-and-comers.

Tables of chess players pore over their games, discuss politics, or provide strategy lessons to up-and-comers.

We end our day back on the Upper West side, sipping wine and sharing tapas on the patio of a little Spanish restaurant. The conversation flows comfortably and comfortingly around relationships and careers and writing projects. We rediscover old intersections, and discover new ones. At one point in the evening, Angela says, “Were we separated at birth?” Maybe so, but we’re connected now, and I can hardly wait to see where the next five days will take us.

This is what literature offers: a language powerful enough to say how it is. (Jeannette Winterson)

If you’ve ever helped someone learn – a co-worker in the next cubicle, a grandchild in your kitchen, the neighbor kid across the fence – you’re familiar with the wonderous “Oh, now I see!” moment. When that light appears, it’s almost impossible not to want to flick the switch on again and again. And when you do, you might realize that the person you’ve taught isn’t the only one who’s learning

After the Aboriginal students in my literature class recognized themselves in Marilyn Dumont’s poem Leather and Naughahyde, (for the back story, see my March 26 post), I knew I’d be spending a lot of Saturday afternoons in the public library, looking for other writing by Canadian Indigenous writers. Since more than a quarter of my students self-identified as First Nations, Metis, or Inuit, I wanted them to experience themselves again and again in the literature I brought to class.

It was simple enough to find a list of authors in the library database, but where to then? I had no idea who most of these writers were. And I needed selections that featured adult characters, yet were accessible enough for some students who struggled with reading. An enthusiastic librarian made suggestions and helped me to sift through the choices. I’d go home with an armload of novels and poetry anthologies, spend the weekend reading, and badger my department head on Monday for book money.

The classroom discussions that this literature sparked were inspiring. Canada’s Indigenous writers portray situations that accurately reflect the often challenging circumstances experienced by Aboriginal Canadians. Their characters struggle with issues of self-identity, addictions, poverty, family fragmentation, and racism. At the same time, they face their challenges with hope, resilience, determination, and humor. It wasn’t only the Aboriginal students who related to these themes. Many of their classmates were equally as captivated. The literature became a starting point for telling our own stories, and our conversations often spilled out into the hallways after class.

After I left my job as a high school upgrading instructor, I continued to seek out literature that told me more about Canada’s First Peoples. Somewhere along the line, what I viewed as my professional obligation had deepened into personal engagement and a sense of civic responsbility. The page-turning stories, complex characters, and powerful, elegant images found their way into my heart. Not only that, this literature offered insights into Indigenous culture and history, deepening my understanding of how colonialism, residential schools, and damaging government policies continue to profoundly impact the lives of Aboriginal Canadians.

I’m happy to share the names of six authors whose writing has helped my students and me to think differently about ourselves, our communities, and our country. The list is partial, and the names are in no parituclar order. I’ve included each author’s Twitter handle, in case you want to follow them that way as well. They’re my personal “go to” authors who have provided me with one or more especially powerful reads. I hope they’ll inspire a trip to your local bookstore or library, and possibly your own journey of understanding into the history of Indigenous people, in Canada or your own country:

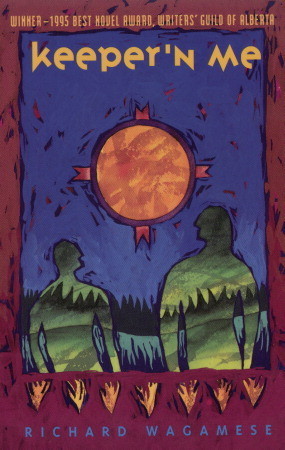

Richard Wagamese (@richardwagamese): Wagamese’s novel Keeper ‘n’ Me was the first full length selection my students and I tackled together. We followed Garnet Raven as he returns to the home from which he had been removed when he was 3 years old. He rediscovers his family, his community and himself with the guidance of Keeper, a friend of his grandfather’s. A touching, hilarious, hopeful story of reconnecting

Richard Wagamese (@richardwagamese): Wagamese’s novel Keeper ‘n’ Me was the first full length selection my students and I tackled together. We followed Garnet Raven as he returns to the home from which he had been removed when he was 3 years old. He rediscovers his family, his community and himself with the guidance of Keeper, a friend of his grandfather’s. A touching, hilarious, hopeful story of reconnecting

Thomas King: My introduction to King’s work came through the book of linked stories Medicine River. Set in a Blackfoot community in southern Alberta, we follow Will, a returnee to Medicine River, and his interactions with friends and neighbors, as they regularly and mostly good naturedly interfere in each other’s lives. King’s more recent, narrative-styled commentaries, The Truth About Stories and The Inconvenient Indian: A Curious Account of Native People in North America expose the roots of the many misperceptions about Aboriginal Canadians and sets the record straight on a whole variety of historical inaccuracies. I enjoy King’s deft weaving of storytelling, factual accounts, and sly humor.

Thomas King: My introduction to King’s work came through the book of linked stories Medicine River. Set in a Blackfoot community in southern Alberta, we follow Will, a returnee to Medicine River, and his interactions with friends and neighbors, as they regularly and mostly good naturedly interfere in each other’s lives. King’s more recent, narrative-styled commentaries, The Truth About Stories and The Inconvenient Indian: A Curious Account of Native People in North America expose the roots of the many misperceptions about Aboriginal Canadians and sets the record straight on a whole variety of historical inaccuracies. I enjoy King’s deft weaving of storytelling, factual accounts, and sly humor.

Joseph Boyden (@josephboyden): I wish that I’d still been teaching when I discovered Boyden’s Three Day Road, My students would have loved it. Best friends Xavier Bird and Elijah Weesageechak leave their Northern Cree community to serve as sharpshooters in World War I France. Their experiences in the trenches and towns test their friendship and their personal resilience. Boyden’s follow up novel Through Black Spruce picks up the thread of Xavier’s family generations later as dual narrators Will Bird and his niece Annie share their separate stories of loss, discovery, and the family bonds that keep them connected.

Joseph Boyden (@josephboyden): I wish that I’d still been teaching when I discovered Boyden’s Three Day Road, My students would have loved it. Best friends Xavier Bird and Elijah Weesageechak leave their Northern Cree community to serve as sharpshooters in World War I France. Their experiences in the trenches and towns test their friendship and their personal resilience. Boyden’s follow up novel Through Black Spruce picks up the thread of Xavier’s family generations later as dual narrators Will Bird and his niece Annie share their separate stories of loss, discovery, and the family bonds that keep them connected.

Marilyn Dumont (@reallygoodbrowngirl): A Really Good Brown Girl, Green Girl Dreams Mountains, That Tongued Belonging – Reading Dumont’s poetry is like walking through an art gallery. I wander back frequently to reconsider specific images again and again. With breathtaking clarity, her words personalize Indigenous issues and help me to appreciate their complexity.

Rosanna Deerchild: This Is A Small Northern Town is a stark poetic portrayal of a girl’s life in a rough scrabble mining town. We accompany Deerchild into the turbulent heart of her family, and on her rambles through the community, where she finds both acceptance and rejection, beauty and squalor among the people and places that touch her life.

Rosanna Deerchild: This Is A Small Northern Town is a stark poetic portrayal of a girl’s life in a rough scrabble mining town. We accompany Deerchild into the turbulent heart of her family, and on her rambles through the community, where she finds both acceptance and rejection, beauty and squalor among the people and places that touch her life.

Katherena Vermette(@katherenav): When I lived in the south end of Winnipeg, my neighbors told me, “Don’t go to the North End. It’s too dangerous.” So when I discovered North End Love Songs, by Winnipeg poet Katherena Vermette, I was hooked. Vermette draws stunning portraits of the people who make the north end their home, finding poetry in girls drinking Big Gulps and young mothers watching over their children at play. A heartbreaking series describes her brother’s disappearance, the police’s indifference, her parents’ grief. I’m reading the book for the second time now, dazzled that so few words can evoke so much emotion.

Yesterday, it was finally warm enough again for me to walk to work. Could spring finally be here, she said, with tremulous hope? And then this morning, I ran across this joyous Steve McCurry tribute to walking. Please enjoy the images and words. Better still, get out and go for a walk yourself!

That’s one good story, that one. (Thomas King, from his work of the same name)

It began with five students who sat on the floor outside my classroom every morning, waiting for me to unlock the door. George*, a storyteller in his forties with a cigarette-roughened laugh, was usually entertaining Cheyenne and Melissa, who giggled behind their hands. Jackson, a tall, slim kid barely out of his teens, his hair combed back into a long, thin braid, sat slightly apart from them, reading a different book every few days. Linda was either issuing off-to-school, cell phone directives to her children, or scribbling notes on a to-do list in her daytimer. When I appeared, they scrambled to their feet, filed to the back of the room, opened their binders, and fell silent, waiting for me to begin the day’s “Prep for High School Literature” lesson.

It was their silence that began to worry me. I thought I had created a classroom atmosphere that welcomed all my students to participate. I’d chosen reading selections that featured adult characters and the complexities of adult life. I’d provided lots of opportunities to discuss what we read. I’d been careful to listen to the students’ responses, and not to make my literary interpretations the “correct” ones. Many of the students had taken a while to find their voices, but most were now participating in our discussions. George, Cheyenne, Melissa, Jackson, and Linda were not.

I knew that all five had ticked off the optional “First Nations/Metis/Inuit” box on their registration forms, so I made an appointment with the Aboriginal student coordinator to ask for advice. She listened thoughtfully to my concerns.

“I wonder if you’re worrying for nothing, Pam. Some of our people prefer to learn by watching and listening. Just because they’re not saying anything doesn’t mean they’re not interested in what’s going on. They’re showing up every day, right? That should tell you they’re getting something out of your class.”

This way of looking at student engagement was new to me, and it partially soothed my worry. But as I walked back to my office, I still wondered if I was doing everything I could to offer these five students the chance to be part of our literary conversations.

A few days later, still puzzling, I ran across an article that talked about the importance of including multicultural literature in a literacy program . I’d read lots of similar articles, but when I got to a sentence that said, “Everyone wants to see themselves in what they read,” I had a sudden realization: Not a single selection I’d chosen for my class was written by an Aboriginal author. Nowhere did a First Nations, Metis, or Inuit character deal with a dilemma. Could it be that the five students weren’t talking because what they were reading wasn’t speaking to them?

I was embarrassed to realize that, even with a degree in literature, I only knew one Aboriginal author – poet Marilyn Dumont. I’d heard her give a reading several years before, and I still remembered the flow of her words, the fire of her delivery. One trip to the public library later, and I had her book A Really Good Brown Girl in hand, ready for my next morning’s lesson.

I told the students what I’d been able to find out about Dumont – that she had been born and raised in Alberta, that she was of Cree/Metis descent, that she was related to Gabriel Dumont. I introduced them to three words they’d need to know to understand the poem I’d chosen: treaty guy, naughahyde, and mooniyaw. I said that I’d read the poem to them, even though as a non-Metis woman, my voice wasn’t ideally suited to the poem’s content. Then, with a glance towards the back of the room, I said I was looking forward to the insights that some of them might be able to offer about the poem’s meaning. I cleared my throat and began:

Leather and Naughahyde**

So, I’m having coffee with this treaty guy from up north and we’re

laughing at how crazy the ‘mooniyaw’ are in the city and the con-

versation comes around to where I’m from, as it does in under-

ground languages, in the oblique way itdoes to find out someone’s

status without actually asking, and knowing this, I say I’m Metis

like it’s an apology and he says, ‘mmh,’ like he forgives me, like

he’s got a big heart and mine’s pumping diluted blood and his voice

has sounded well-fed up till this point, but now it goes thin like

he’s across the room taking another look and when he returns he’s

got ‘this look,’ that says he’s leather and I’m naughahyde.

“Well, if you ask me, this woman needs some serious personal development classes.” Linda’s voice. “I’m Metis, and I never apologize to anybody for it.”

“Oh, come on, Linda.” Melissa from across the aisle. “You know this happens all the time. Treaty guys always think they’re better than us, like they’re the genuine article and we’re not. Right, George?”

No response, except from Cheyenne. “What bugs me is how we’re all fighting about who’s more important. Why can’t we all just get along?”

“Hey, you guys.” Paramjeet, cranked around from the front of the room. “This sounds kind of like the caste system we have in my country. Some people won’t even talk to people who aren’t as high status as they are.”

It’s been more than ten years since this small but mighty poem flung open doors for my students – and for me. It launched me on a learning path that I`m still following – to better understand Canada’s First Peoples through Indigenous words, visuals, and the performing arts. In the coming weeks, I hope you`ll accompany me on that road. It`s been a fascinating journey so far, and I can just about guarantee that you`ll hear more than a few good stories.

*The students’ names are pseudonyms.

**This poem is reprinted by permission of the author. You can hear Marilyn Dumont read a selection of poems from A Really Good Brown Girl at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uW93BoeGQ-I . Leather and naugaahyde starts at the 12:00 mark.

This is the third post by guest blogger Christie Robertson, in which she explores some of the questions of pre-motherhood through a dog ownership lens. Enjoy!

I remember it vividly. I was in the truck, with Molly in the back seat barking madly right in my ear. I whipped around and yelled wildly, on the verge of tears, “Shut up! Just shut up! What the @*$% is wrong with you? Shut up!” My voice cracked with the last shut up and Molly was so taken aback, she suddenly fell quiet.

Directly building up to this melt down, I had tried to take her to cheer on a friend at a running race. Molly had barked all the way there and run away when we arrived. I never did make it to the race meet point, but rather got back into the truck and was driving home defeated amidst her yammering. I should point out that this is not her normal behaviour; while she does sometimes bark in the car, she had never acted anything like this. And my normal behaviour? I’ve taught a class of 15, 14-year old boys who all actively and routinely tried to disrupt the status quo for no reason other than it was more fun than learning, and my blood pressure stayed regular-or at least I could make it appear this way on the outside. So why on this day did I lose it on a single, barking dog with love in her chocolate brown eyes? Let’s call it an off day for both Molly and me.

(One example of Molly barking uncontrollably at something stupid…statues of bears. This time it was funny. Usually it’s not.)

My husband Matt commonly says, “You can’t really get mad at the dog. She has a brain the size of a walnut. She doesn’t know any better.” Unfortunately, I think her mentality is why I, on the odd occasion, have boiled over. Even on good days, it feels like Molly has the cognitive capacity of a two-year-old and I have a hard time coping with this.

Molly did finally give up on the ball and let me write this post. Every 30 seconds I would hear a soft, pathetic, little whine escape her lips as she moped on the basement stairs outside the office.

Why doesn’t she get that nobody likes the sound of her bark? Why doesn’t she understand I don’t want to be woken up to her whines at 2am? Even as I write this post, she is barking at me because she wants to play ball. Why can’t she figure out I’m busy and ignoring her?! So with our new baby on the way, I wonder: Am I going to lose it on the child like I have with Molly?

Maybe the more realistic question is, do I accept the fact that I will probably have moments of total yelling insanity, or work proactively to find strategies to prevent my own meltdowns? Or, is it acceptable to do both?

I’ve heard many times in many different contexts, the first step to solving a problem is admitting there is one in the first place. So, I am officially going on record to say that dealing with people/animals/things that can’t rationalize and act maturely has the potential to send me into a tornado of rage (note the word ‘potential.’ I’m not a total hag).

Usually, I intellectualize my conflicts, using reason to block out emotional stress so I can work towards a resolution. I work through the problem in my mind until I come to a possible solution(s) and, if necessary, put the solution into effect with the involved parties’ feedback and assistance. However, when the other party isn’t willing or, in the case of Molly or a child, isn’t capable of giving me feedback, I don’t know what to do. The emotion creeps back in and, depending on the severity of the situation, I might yell. This is particularly true if the problem is repetitive in nature or I perceive it as nonsensical–like a dog yapping constantly at nothing. Perhaps it is time for me to research a new way of tackling conflict. Any suggestions from my parent readers out there?

Step 2? I plan to do a bit more research into children’s cognitive and emotional capacity. While it feels like Molly is “acting like a 2-year old” she certainly isn’t a person. Instinct, rather than emotion, is what makes her react and this is very different from a child who is not only feeling emotion but learning how to react to these emotions. I figure if I can at least understand where the child is coming from, this may help me diffuse my temper. A friend told me about a book titled The Science of Parenting, by Margot Sunderland. It discusses the neuroscience behind child rearing. This is first on my reading list and probably won’t be the last.

I know I won’t be that parent that yells all the time – it’s just not in my nature – but I think it’s foolish to think it will never happen. I’m hoping my research will help, and at the very least I will try not to beat myself up when despite my best efforts, I lose my temper with my child. And if all else fails, I will just have to keep reminding myself the baby will eventually grow into a rational human being, even if it takes 25 years. I wish I could say the same about Molly.

In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit. Not a nasty, dirty, wet hole, filled with the ends of worms and an oozy smell, nor yet a dry, bare, sandy hole with nothing in it to sit down on or to eat: it was a hobbit hole, and that means comfort (J.R. R. Tolkien, The Hobbit).

As a little girl, I was a passionate believer in the world of the Little People. My grandmother, always a supporter of my imagination, gave me The Giant Golden Book of Elves and Fairies for my sixth birthday, and I spent hours poring over the illustrations: a troop of elves, parading through a misty evening forest, lighting their way with firefly lamps; an elderly fairy, sitting in a rocker outside her second-hand shop; leprechaun cobblers hard at work in an underground room of tree roots. I looked every day for some evidence that Little People had visited my prairie yard. When I didn’t find any, I took the plastic charms my dentist had awarded me for good behavior and hid them among the cabbage leaves in our garden. The next morning, I’d delight myself by pretending that some wee folk had left their belongings behind during the night.

So, last December, when I saw an ad for a session at the Muttart Conservatory that offered me the chance to make my very own Hobbit hole, my six-year-old self tugged at my sleeve and said, “Let’s go!” She and I counted down the days, double-checking the date on the confirmation form more often than we needed to.

When the big night arrives, we are greeted at the classroom door by a young man who bears more than a slight resemblance to Elijah Wood’s Frodo Baggins. He is Eric Gibson, head designer of the Muttart’s feature pavilion, and one half of Axis Mundi Artistry, an Edmonton horticultural business that specializes in creating and teaching others to design living plant arrangements.

Our fellow Hobbit hole adventurers soon join us: four young couples, a gaggle of twenty-something women in toques and geek chic glasses, a grey-haired gentleman. Although there appear to be only two children among our group – one accompanied by her grandmother, the other with his dad – the spirit of anticipation in the room tells me the little person who urged me to take this class has lots of company this evening.

Eric supplies everything we need for our journey: a hefty ceramic planter; pebbles, charcoal and soil; moss, bonsai trees, and babies’ tears; tiny chimneys, round doors, and supplies to make miniature slate patios, fences, benches, and brooms. The room comes alive with the perfume of damp earth and the buzz of delighted creation. We mound the house foundation soil in our planters, covering it with chicken wire, more soil, and emerald moss. Then, we begin designing the exterior landscapes, carving legs for the benches, wrapping wire around fence posts, and planting trees.

Like all good adventures, there are decisions to make and a few challenges. “Honey, how about if we make our patio on the roof, instead of in front of the house?” “Dad, I didn’t want the fence to look like that.” “My door doesn’t want to stand up straight.” Eric offers his assistance and we problem solve with each other. I discover I’ve left very little room for my hobbit to have an outdoor living space. The couple who are sharing my workbench tell me they’ve got the same situation. “Oh, well,” says the young man, his ‘Death before Dishonor’ T-shirt a seeming mismatch for his cheerfulness. “My house is rocking the square footage instead.”

Like all good adventures, there are decisions to make and a few challenges. “Honey, how about if we make our patio on the roof, instead of in front of the house?” “Dad, I didn’t want the fence to look like that.” “My door doesn’t want to stand up straight.” Eric offers his assistance and we problem solve with each other. I discover I’ve left very little room for my hobbit to have an outdoor living space. The couple who are sharing my workbench tell me they’ve got the same situation. “Oh, well,” says the young man, his ‘Death before Dishonor’ T-shirt a seeming mismatch for his cheerfulness. “My house is rocking the square footage instead.”

Two hours later, we’re standing back to admire our own and each other’s creations. The Shire never experienced the minus 20 temperatures that are tyrannizing Edmonton, so Eric advises us to wrap our little houses in garbage bags, breathe warmth inside, and get them out to our cars as quickly as we can. I join the line of vehicles pulled up to the Muttart’s entry, dash inside, pop my car’s trunk, and slip the hobbit home inside.

Now, it sits by my place at our dining room table. On work mornings, as I try to stretch the time before swapping home for a windswept bus stop, I wonder if my resident hobbit is enjoying first breakfast at the same time I am. Maybe he will come out to have a pipe on the bench I built for him, or to tidy up the patio with the whisk broom I constructed. Maybe he has already left on an adventure into harsh and uncharted lands, misses the comfort of familiar places, and longs for spring. If that’s the case, I hope he has a good friend to remind him that both are as close as his memory, and may be nearer than he realizes.

Now, it sits by my place at our dining room table. On work mornings, as I try to stretch the time before swapping home for a windswept bus stop, I wonder if my resident hobbit is enjoying first breakfast at the same time I am. Maybe he will come out to have a pipe on the bench I built for him, or to tidy up the patio with the whisk broom I constructed. Maybe he has already left on an adventure into harsh and uncharted lands, misses the comfort of familiar places, and longs for spring. If that’s the case, I hope he has a good friend to remind him that both are as close as his memory, and may be nearer than he realizes.

Do you remember the Shire, Mr. Frodo? It’ll be spring soon. And the orchards will be in blossom. And the birds will be nesting in the hazel thicket. And they’ll be sowing the summer barley in the lower fields… and eating the first of the strawberries with cream. (The Lord of the Rings, Return of the King).

This morning, my WordPress colleague over at Invisible Horse shared this inspiring and colorful crocus symphony from Bronte country. With March 1 coming in tomorrow like a T.Rex., please enjoy her words and photos. They will renew your faith that spring will come!

This time of year is the hardest, when the skies hardly ever seem to be anything but grey, and the drab dullness of wet woods and sodden fields is only occasionally lifted into life by the sudden brief appearance of the sun. I’d been yearning for colour so badly that it had become a real sensation of emptiness, like hunger or thirst.

It had been raining for days and I hadn’t been out for more than a few minutes at a time, so when I got to the park again after almost a week I was completely taken by surprise – carpets of colour; purple and lavender and white, flashes of bright emerald green, and the tiniest punctuation of yellow. There was even a moment or two when the sun came out from behind the clouds. I got down on my knees in the wet grass and pushed my face…

View original post 135 more words

Still I have the warmth of the sun within me tonight.

– The Beach Boys

Tonight, the weather forecast is the same no matter where I look. The Weather Network has the most dire prediction – an overnight low of -31C, the wind making it feel like -38 . Environment Canada is marginally more optimistic, calling for a low of -28, with a wind chill of minus 3o. AccuWeather agrees with those numbers, and offers the assessment that these are “bitterly cold” temperatures. Inexplicably, it also warns us of a “cold wave starting Thursday. “

Meanwhile, I’ve got July in a crystal dish on my kitchen counter.

Not the whole month, of course. Just a few minutes spent in our backyard raspberry patch, the early morning sun already warm on my neck, the neighborhood Sunday serene. That day, bitter cold only existed in my imagination and our freezer, where I balanced cookie sheets covered in wax paper and raspberries on top of boxes of popsicles, packages of rib eye steaks, and a half bag of perogies hoarded since Christmas. In less than an hour, I’d captured the sunny sweetness of that morning inside dozens of berries, scooped them up, and sealed them inside a large plastic container with a tight-fitting lid.

There they slept for 7 months. Tonight, it’s time to release their magic. This takes a warm kitchen, patience and a keen nose. At first sniff, their aroma is still locked inside ice crystals. A half hour later, and a faint pink tickle wafts up. Thirty minutes more, and I’m inhaling their full-throated, ruby harvest perfume. The time is ripe.

Now for the Dairy Queen™ soft serve. The young guy behind the counter looked at me a bit quizzically earlier this evening when I ordered a single serving to go, no topping. I pull it out of the freezer, and let it thaw just until it begins to puddle slightly in the plastic cup. I spoon the white drifts into a second dish, and place the raspberries on top, a painter daubing crimson on canvas.

With closed eyes, I savor the first spoonful. The mingling of creamy satin sweetness and juicy berry tang is full summer on the tongue. Another mouthful and my kitchen window springs open. The air is July gentle, and my neighbor’s two-year-old granddaughter is shrieking with delight as she splashes in her grandparents’ wading pool. A third bite, and flowers in full bloom appear outside my back door , gushing over the sides of their containers.

Too soon, I’m scraping the bottom of the dish. All I see now outside is the wind bouncing the dark tangle of elm branches against a chilly sky. A frozen white poinsettia languishes by my neighbor’s back door, its gold foil wrapped pot glinting faintly under the porch light. But, I’ve renewed my faith that spring will come, and summer will follow. And if I need another reminder, Dairy Queen is open until 10 p.m. and my frozen raspberry cache is far from depleted.

Too soon, I’m scraping the bottom of the dish. All I see now outside is the wind bouncing the dark tangle of elm branches against a chilly sky. A frozen white poinsettia languishes by my neighbor’s back door, its gold foil wrapped pot glinting faintly under the porch light. But, I’ve renewed my faith that spring will come, and summer will follow. And if I need another reminder, Dairy Queen is open until 10 p.m. and my frozen raspberry cache is far from depleted.